The basic facts: the 155,000 BPD oil refinery owned by ExxonMobil and located in Torrance, California (suburb of Los Angeles) had a large but non-fatal explosion in February, 2015 when hydrocarbon vapors that had flowed into an electrostatic precipitator system ignited and exploded. Four workers were injured. The refinery has been operating at reduced-capacity ever since, with the fluid catalytic cracker (FCC) unit shut down until adequate repairs are made and government regulatory agencies are satisfied that the refinery can operate safely again.

Just two days ago (13 January, 2015), a public meeting was held in Torrance at which the Chemical Safety Board presented its findings on the explosion. A newspaper account of that meeting can be read here (see link).

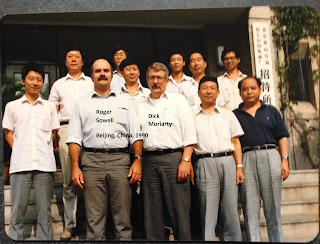

As a former practicing, and consulting refinery process engineer for many years, and much experience in dozens of similar refineries world-wide, I take keyboard under fingers here to offer some insights. First, a word of my background and qualifications that I have never before shared in public.

Many years ago, in

We had (and still have, in my case (note: sadly, Dick Moriarty passed away) ) extensive knowledge of oil refineries, and had performed many such operating and profit improvement studies on refineries world-wide. We looked at refineries from start to finish, crude storage and distillation, to products blending and all off-sites units. What we did not know was that the Chinese national television station brought a full crew with cameras, lights, and microphones to record our introductions on our first morning of the Chinese refinery improvement consulting project. The head Chinese dignitary made a speech on camera, and a few others made speeches, then a translator told my boss that he was next. Just before my boss spoke, the last speaker spoke Chinese first, then English for our benefit. He described the process just above of the Chinese effort to improve their refineries and their need for an outside opinion. He ended by saying, "And now our distinguished foreign consultants will make their comments." (I will never forget that phrase, Distinguished Foreign Consultants.)

My boss looked at me, and said to the camera something very short, thanked our hosts for selecting us, and ended by saying, "and now my associate Roger Sowell will describe the approach we take in our refinery profit improvement studies." I was caught with no time to prepare, or think of what to say. The lights were bright, the microphone was now in front of me, and the camera lens was aimed right at me.

|

| Richard "Dick" Moriarty and Roger Sowell with Chinese refinery management at Yanshan Refinery Beijing, People's Republic of China, 1990 |

So, I echoed my boss' sentiments on how happy I was to be in China, for our company to be selected after a world-wide bidding process, and delighted to have the opportunity to work with the wonderful Chinese engineers and managers to study their petroleum refineries. I described briefly the process we used, first to go over each process unit with the management to gain an understanding, then take the operating data back to the States for analysis using our proprietary computer software and our engineering experience.

I seldom relate this story of the Chinese refinery consulting at Yanshan Petrochemical Corporation near Beijing. My point in relating this now is that I have the background to offer a considered opinion on events such as refinery explosions like the one at Torrance in February 2015. (The Chinese company was not the only major international oil company that hired us, as we also consulted for PetroCanada, AGIP in Italy, Total in France, and many others).

There are calls presently in California to tighten the regulatory scheme on safety in oil refineries. As can be seen on the Chemical Safety Board's web pages, the CSB is comparing the Torrance refinery explosion to the earlier Chevron refinery fire and explosion in Richmond, California. There is a concerted effort to have oil refineries redesigned and built in what is referred to as an inherently safe manner, or to use "inherently safer design." One example of inherently safer design is to use non-corrodible materials of construction so that piping and vessel wall thickness does not decrease over time, leading to a rupture, leak, fire, or explosion. Another example is to provide safety interlocks so that a fluid cannot flow because a valve cannot be opened when it is unsafe. There is a great body of literature on inherently safer design. It should be noted, and I make this point in my speeches on the matter, that requiring non-corrodible materials is extremely costly, as for example using titanium for all wetted piping and vessels instead of carbon steel or stainless steel.

What occurred in Torrance at the refinery was a combination of bad human judgement and equipment failure. Essentially, the FCC has three sections, a reactor section, a main column, and a vapor recovery unit. The reactor section itself has two sections, the reactor and regenerator. All of these are connected by various pipes. In normal operation, feed oil enters the reactor, contacts catalyst and reacts, the products are separated from the spent catalyst, and the products flow into the main column for separation into various streams. Vapor products from the main column are routed to the vapor recovery unit, where valuable products are separated from light gases. The light gases are generally burned in the refinery as fuel. Spent catalyst from the reactor is sent to the regenerator, where the catalyst is contacted with hot air that burns carbon off of the catalyst. The regenerated catalyst is recycled back to the reactor. Combustion gases from the regenerator are sent to a power recovery turbine and from there to an air pollution control system, the electrostatic precipitator that exploded in Torrance. This description is necessarily simplified, as there are many more items of equipment in an FCC unit.

I worked in and with dozens of FCC units in my operating and consulting career. They are fascinating units with many challenges and great opportunities for profit.

The problem in Torrance occurred when part of the FCC unit was shut down for repairs, the reactor section. However, and this is crucial, the main column was not shut down. It is always required that flammable hydrocarbons be kept away from any work area, and the ExxonMobil team tried to do that. They closed the correct valves, and injected steam into the reactor to form a barrier or seal against the hydrocarbons in the main column. However, according to the CSB report released on 14 January 2016, (yesterday as this is written), steam leaked out of the power recovery turbine, or expander as it is also known, into the work area. This interfered with the workers and may have been unsafe in itself, since a cloud of steam in a refinery obscures visibility and may make it difficult to breathe. The steam rate was reduced so the workers could perform their tasks. see link to CSB report.

Meanwhile, and unknown to the personnel, a critical valve leaked and allowed hydrocarbon vapors to pass from the main column, through the reactor, pass the leaking valve (spent catalyst slide valve), through the regenerator and power recovery system and into the electrostatic precipitator. A spark ignited the vapors, and an explosion resulted. All of this is explained in great detail in the CSB report.

For further context, there are more than 100 FCC units in the US today, with many more world-wide. Almost every modern refinery has an electrostatic precipitator to meet the stringent air pollution requirements. These FCC units operate approximately 3 years before being shut down for planned maintenance. There are of course many other unplanned shutdowns, also. But, using just 100 FCC units, and 3 years between shutdowns, there are approximately 33 units shut down each year, or roughly 3 every month. Yet, there are very few explosions that result from these shutdowns, and subsequent startups. One could argue that most planned shutdowns do not leave the main column full of hydrocarbons, so there is no need to insert a steam blanket to keep the hydrocarbons away from the workers. Yet, there have been other occasions during which the procedure was performed with no harm or damage. Clearly, then, the procedures are acceptable but something was different in this case.

It appears, based on the CSB description of events, that the problem would not have occurred if the spent catalyst slide valve had not leaked, or if the steam had not leaked out of the expander, or a combination of both.

It would be an over-reaction for regulating agencies to enact new, burdensome rules on the entire industry in an attempt to prevent an accident that almost never occurs. Yet, there are calls for exactly that, to make the refining industry be subjected to inherently safer design.

A better approach is to increase the penalties and fines for those who violate the existing safety regulations, so that a violation will be so costly that the workers, and managers, exercise extreme caution. One example, was a refinery management that was interested in the impact on their US refinery of an explosion similar in scope and damage to the one in March, 2005 at BP's Texas City Refinery. That explosion killed 17 people and hospitalized more than 100 others. The injuries, deaths, and damage occurred after human error caused flammable liquids to overflow a vent pipe, vaporize, reach an ignition source and explode. In that case, the equipment was fine but the humans made errors. That explosion cost BP several billion dollars in fines, repairs, and legal settlements. Such a sum would bankrupt many smaller companies. That sobering fact was what was brought home to a different company. Safety is vital, not only for the safety and lives of the employees, but surrounding communities, and also the ongoing viability of the company in many cases. see link to BP Texas City Explosion of 2005.

In the Torrance explosion, a combination of human decisions and equipment malfunction were at fault. In retrospect, it would have been better to shut down the main column, and insert a blind flange in the line at the spent catalyst slide valve. In short, make it almost impossible for any hydrocarbons to leak into an area where an ignition source could create a fire or explosion.

UPDATE 1: 16 January 2016 - The Chair of the Chemical Safety Board wrote a letter to the editor opining that California refineries need more regulations to force them to operate safely (my paraphrase). see link to the letter to editor.

Chairperson Sutherland wrote:

"If finalized as currently written, California’s new safeguards (i.e. regulations) for oil refineries would strengthen the state’s oversight by requiring management to take steps to reduce risks to the greatest extent feasible. And the draft regulations include some important safeguards on the forefront of refinery safety, such as requiring incident monitoring and tracking data.

I eagerly support Gov. Brown and the state Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) for initiating these changes. I believe the actions being taken here in California are some of the most substantial positive safety changes happening right now."

Chairperson Sutherland added that "California can lead the nation in refinery safety," an indication that the new California regulations would, or should, be extended to all US refineries.

I note in passing that Chairperson Sutherland has zero technical education, as her biographical sketch available online states she holds a BA in Political Science/Art History, as well as an MBA (in Information Technology) and a JD. She is an attorney licensed in Maryland. Her only brush with non-computer technology appears to be a brief stint at Department of Transportation's Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. She has been Chair of CSB since August, 2015, a total of six months as of this date.

-- (end update 1)

Here ends this article for today. There may be additional updates.

Roger E. Sowell, Esq.

Marina del Rey, California

copyright (c) 2016 by Roger Sowell, all rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment